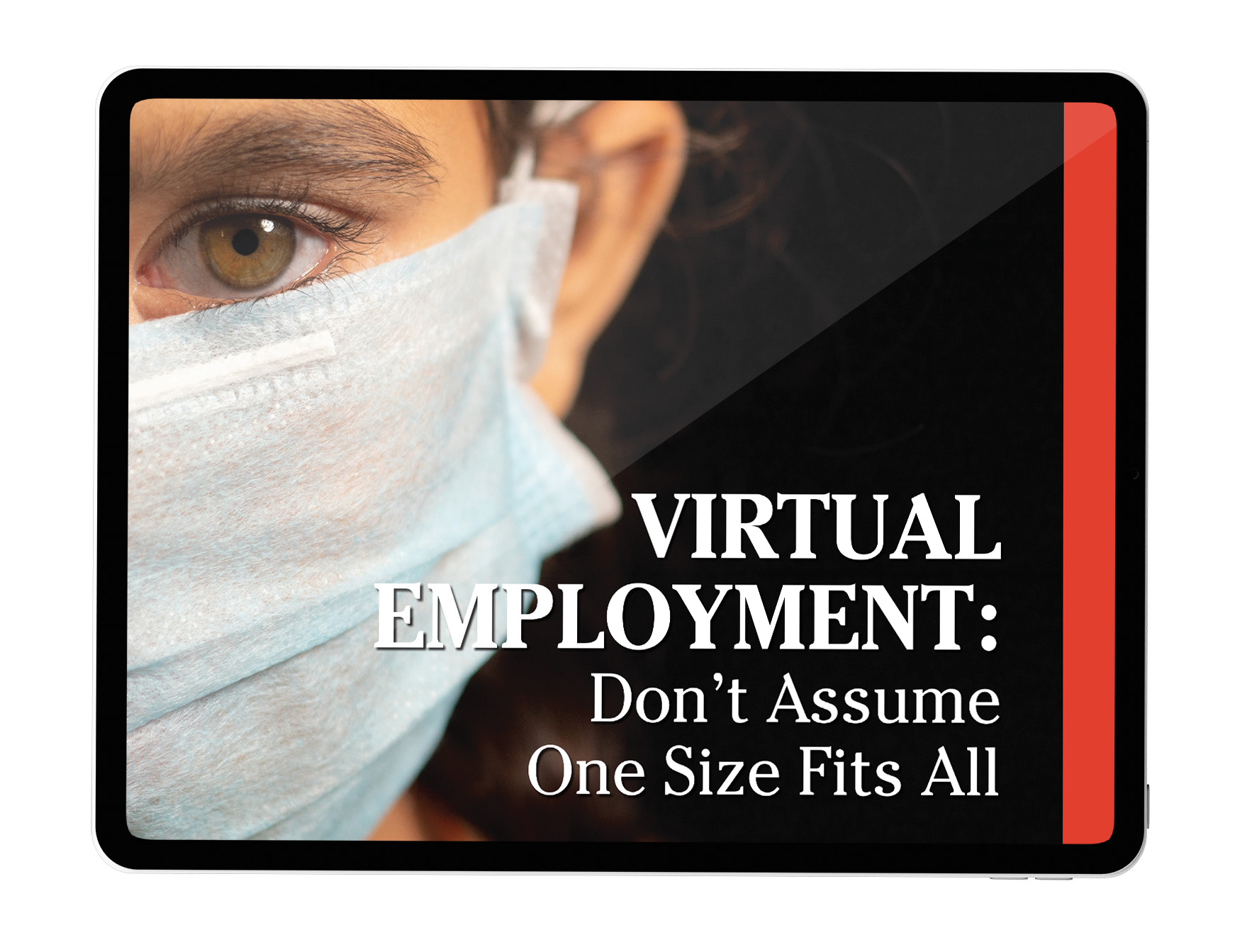

The great, big switch to remote work has clearly shown us that working in an office every day is not necessary for many businesses. Likewise, companies and employees now widely view flexibility and work-life balance as essential. But just how far and flexible are we heading?

This question has come to the fore following a recent study that shows shorter workdays resulted in not only happier workers, but also productive ones.

The study, published by Autonomy and the Association for Sustainability and Democracy, assessed 2,500 employees in Iceland, who reduced their working hours from as high as 40 hours per week, to 35-36 hours weekly, without having their pay cut, during trial periods from 2015-2019. Results showed:

- Worker’s well-being greatly improved, including lower reported stress and burnout, as well as better health and work-life balance, with many workers saying it was easier to do household errands and make more time for themselves

- Productivity remained the same or improved at the majority of trial workplaces, which spanned a diverse range of industries and workplaces

- Following the successful results of the trials, 86% of the country’s workforce are now working shorter hours or gaining rights to shorten hours

- As of June 2021, more than 170,200 unionized workers in Iceland, out of a working population of 196,700, are covered by contracts for shorter working hours

“This study shows that the world’s largest ever trial of a shorter working week in the public sector was by all measures an overwhelming success,” said Will Stronge, Director of Research at Autonomy. “It shows that the public sector is ripe for being a pioneer of shorter working weeks – and lessons can be learned for other governments.”

You might be inclined to think that Iceland is vastly different than the United States. And that’s a fair point. But many countries, including members of the G-7 and other highly industrialized nations, are actively seeking to attempt lowering the amount of time people work in a week.

For example, the government of Japan, a country notorious for work-related burnout, is putting plans together to encourage companies to cut their work weeks to four days. More than 40 Members of Parliament in the United Kingdom requested a commission to explore a similar project to the one carried out in Iceland.

Spain is about to explore a four-day week. The Spanish government has agreed to a 32-hour week of work that would not reduce employee pay. About 200 companies are expected to take part in a pilot program involving anywhere from 3,000 to 6,000 workers, with the government putting $60 million towards the initiative.

The pandemic taught us, in the most tangible terms, that employee flexibility and work-life balance is critical and contributes to productivity. To continue on this successful path in the future, perhaps we should look at the lessons learned in other nations and consider work weeks that place a premium on employees’ well-being.